It’s early in the morning of April 17th 2014, and all the villagers are ready. They have collected indigenous Trau (Vernicia fordii) wildlings for re-afforestation and prepared new boundary markers to replace those removed by the company. With firm expressions and determined eyes they set off, together, as a community, for their communal forest. They intend to take back their land that was illegally grabbed by Que Phong Rubber Company, and repair the damage done by the company’s machines and workers.

I accompany them on the walk through their sacred watershed forest. It is a beautiful time of day, the air feels cool and fresh, and the first rays of the sun penetrate the canopy. As we walk, the mood lightens and I hear laughing and excited chatter. Someone starts to sing and soon many have joined in. I am amazed by how many women have come along. A companion tells me that nearly every single women in the village is talking part. Although the women have other important things to do, he says, they made the decision to come, not only to show solidarity but also because the forest is important to them. After all, it is they who depend on the forest for many food and medicinal non timber forest products.

We fall silent as we come to the devastated area, taking in the destruction, squinting beneath the bright sky. The hillside is laid bare before us, mature trees logged and removed, only clumps of rough grasses visible beside the young rubber planted by the company. Already I can see soil loss in bare areas and only imagine what the future might look like if this company is not stopped. But the villagers are positive and well organized, and quickly go confidently about their tasks. One group sets about replacing boundary markers bulldozed by the company, whilst others weed and prepare holes to plant the Trau trees.

I join in the task, filled with admiration for these people’s resolve, and impressed by the decisions they have made. The people of Pỏm Om village (and surrounding villages), had not taken this action lightly or in haste. It was a considered move after almost a year of struggle with the company, following legal process. Rather than just ripping up the illegally planted rubber trees, the villagers have decided to plant quick- growing corn to help hold the soil and offer some protection against rain and sun for the very short term. They chose indigenous Trau because of its environmentally friendly characteristics. It is relatively fast growing, forming a good protective canopy layer, but its leaves and branches are quite soft. When they fall to the ground they provide good structure for the soil and are broken down quickly providing accessible nutrients. The added benefit is that the seeds of the tree can be harvested and sold for their oil. The villager’s strategy aims to regenerate forest and protect the soil, at the same time making it difficult for the rubber to thrive. It may be early days, but it seems these thoughtful people have turned adversity into a positive for all the community.

Hanh Dich villagers replacing boundary markers and planting indigenous trees in encroached area

Villagers re-setting boundary markets and preparing to plant Trau wildlings

As the work progresses, I feel a lightening of spirits. This is their land, not just because they have lived here for a long time, protecting the forest and water source, but also because they have legal ownership, a ‘red book’ for 50 years of communal ownership and management. Yesterday, for the third time in a year, Hanh Dich CPC stood by the villagers, confirming again their right to use and manage this forest, and labelling the actions of the rubber company criminal.

In a well- reasoned and important response to a demand by Nghe An Rubber Company (which owns Que Phong rubber company) to hand over the land, the District Peoples Committee told the company that their actions were illegal for six reasons. There was no land use planning approval for rubber in this area; the company did not have the necessary Land Lease Contract which it must have before planting rubber; it did not have the necessary decision for forest use conversion which needs to be issued by the Province; no Environmental Impact Evaluation had yet been done, which is required before any investment of this kind; the company needed to pay any necessary taxes and fees to government which they have not done, and planting rubber in this area would be illegal anyway because it is sacred forest protecting water supplies, full of herbal medicinal plants used by ethnic minorities and cannot be cut down. Whilst they were reading this letter, I could almost visibly see the villagers’ confidence growing

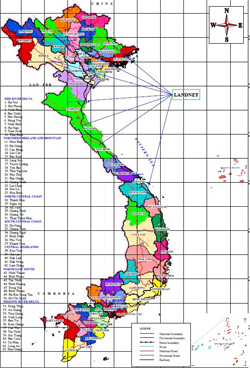

It amazes me to think back over the last year’s events, the arrogance and bullying methods of the rubber company, and how they think they can ignore the law so blatantly. Yet, I have seen the community’s confidence grow as they faced this company, not alone, but with the unswerving support of LISO and LandNet. This was a test-case for LandNet, using the strategy of following legal and administrative process, building the capacity of local people by informing them of policy and their rights, and helping them to lobby on their own behalf, using due process. With LandNet’s support the villagers and commune established a good relationship with the District, requesting their assistance. The District itself showed a good grasp of their responsibilities whilst attempting to resolve the issues through negotiation.

Yet the company revealed its purpose by its actions, and persisted with its illegality. This was no mistake, this was deliberate. What the company didn’t count on was the strength of the villagers supported by LandNet. After the first illegal encroachment in May 2013 the villagers confronted the rubber company director, who admitted the actions were wrong. Yet, in July the same director asked the villagers to accept what the company had done, “as it had already happened”. He also wanted to recommend to Quế Phong District People Committee (DPC) to re-allocate this illegally planted rubber area to the company for long-term use rights and management. More negotiations with the company went on, and promises and apologies were offered by them, yet they did nothing to right the damage or remove themselves.

Finally, frustrated by the rubber company’s stalling tactics, on 21 August 2013, Quế Phong DPC sent an Official Decision No. 654 to Hạnh Dịch CPC, Rubber Enterprise and Pỏm Om Village Management Board. They asked the Rubber Enterprise to (1) stop encroaching community forest and land and remove machines from the village; (2) remove all planted rubber trees from the community land and return the land to the community; (3) coordinate with local authorities when implementing planning to avoid the kind of mistakes that happened in Hạnh Dịch; (4) strictly follow legal procedures and prepare reports related to environmental impact when implementing industrial trees projects of over 50 ha in area. This is in reference to Decree No 29/2011 issued by Prime Minister stating that projects have to report on environmental impact and environment protection commitments.

Yet three months later, at the end of November 2013, the rubber company moved again, taking more land from Pa Co and Pa Kim and Pom Om villages. This was clearly an attempt by them to provoke the community, but with the help of LandNet, village leaders followed process. The District again wrote to the company telling them to leave the land.

In an almost identical response to that of May 2013, the director of the company admitted the encroachment, said sorry, but then suggested the villagers lease the land to the company, as “it has happened anyway”. In later meetings the companies were asked to stop illegal encroachment and implement instructions from the district. Up until today, they have not paid any compensation, neither have they removed their rubber trees.

LISO and LandNet will continue to be involved in this case, looking for lessons learnt, supporting the villagers of Hanh Dich. Clearly we have followed a process, and will continue to do so. The actions of the villagers have been reasonable, and good relationships have been established and maintained with local authorities. Villagers have remained calm in the face of provocation from the company, and constant information updates by LandNet and support from LISO means they have felt connected and secure in their rights.

For LISO, the experience convinces us of the continued need to educate villagers post allocation (through discussions and awareness raising) of their rights, and of policy which supports their ownership and management of forest land. We will also examine the involvement of all stakeholders in the forest land allocation process, to ensure that there can be no danger that companies are unaware of land rights in areas in which they wish to operate, and that authorities are well aware of their duties in the event of problems arising.

LandNet member.jpg) Hanh Dich villagers replacing boundary markers and planting indigenous trees in encroached area

Hanh Dich villagers replacing boundary markers and planting indigenous trees in encroached area Villagers re-setting boundary markets and preparing to plant Trau wildlings

Villagers re-setting boundary markets and preparing to plant Trau wildlings