ADVOCACY

Chau Ma’s requests for land for cultivation turned down whilst rubber companies get the green light for plantations on primary forest

- On 29th September, VTV1, as part of its “Tiêu Điểm”, or “Hot Issues” nightly programme, showed the plight of the Chau Ma ethnic minorities and the destruction of their ancestral forest by logging and rubber companies. They highlighted how bureaucratic processes allowed primary virgin forest to be logged on a large scale and replaced by rubber plantations, whilst denying the traditional owners and protectors of the very same forests any rights over it. Ironically, the reason given by local government for denying local people land rights was that the forest was primary forest and needed protection, so couldn’t be allocated to them.

Hot Issues pointed out that the forest re-classification process as it was being practiced was clearly destroying the forest. Villagers depended on the forest, but companies were now profiting from conversion.

The Chau Ma have now been moved – ‘resettled’ - three times by the government resettlment program, but still have little land. They are now dependent on companies offering them work on their own ancestral forests and land. Their watershed forests, carefully preserved by them for hundreds of years, are disappearing and being replacing by larger and larger rubber and coffee plantations. Village leader Mr K’ba said, “This is primary forest, rich forest. We have been protecting it for a long time, but it is being cleared, and it is really affecting our lives - no forest, no water, no environment.”

Local people now resettled in the sadly-named Thôn 3 or ‘Village No. 3’ in Loc Bao commune, Bao Lam district, Lam Dong province said that there were 17 different companies [1] operating in the basin of these watershed protection forests.

Traditionally the Chau Ma had 6 different villages named by them: “Phi Sar Dă Rơ Yal”, Pru, Sar Niêr, Đing Siết, Bư Đưng, and Prơng Nộp. After resettlement, their traditional structure was changed along with village names. Their villages were merged and divided into two villages renamed by the state “Thôn 2” and “Thôn 3”.

Local people weren’t allocated forest and land for their traditional cultural practices or even for cultivation. Of 280 households containing 865 Chau Ma people, it is estimated around 40% are hungry for up to 6 months of the year. With little land for cultivation, they have to work as labourers on their own land on virtual starvation wages (around $1 a day), which even then might be delayed or not paid. The other 60% of the population have some poor land, mostly not wet rice land (average 700 m2 per household). Despite working hard, these people are also very poor without enough rice for the whole year.

Local people said: “The first time we were asked to move out of our ancestral land in 1978 we were put into a new environment where we did not know what to do for a living. The lifestyle was strange, different from our traditional cultural life. We were unhappy. We missed our village and our ancestral land. We missed our sacred forest. We had nowhere to pray for good weather, a peaceful life, abundant crops, more and healthy pigs and chickens, no one suffering from illness, no one destroying the forest so that they could live, breathe and protect the forests, see our children growing well, protect our ancestral traditional culture and our consolidated community”.

They continued: “After these unhappy years, we decided to return to our own land and forest in 1984 and lived there until 1992. Unfortunately over the next four years, from 1992-1996, we were forced to to move out again. They told us it was for our own good, as we did not have electricity, schools, roads or clinics.

“The fact is we miss our ancestors and want to live on the land inherited from them. We want to live our lifestyle and preserve our Chau Ma traditional identity. Our lives cannot be separated from our forest. However, as you can see for yourself, our forest and land are now being controlled and used by companies. What we should do to let our children understand and practice our traditional culture? We are worried about our daily life which is under threat. We could not stay in the houses built by the State, they feel unsafe to live in and are likely to collapse at any time. We had to build other houses. Though they are small we feel safer to live in there”.

According to Hot Issues, since the last resettlement, the Chau Ma ethnic minority have asked the state 3 times to allocate the forest to them for protection. In 2001 there was no response. In 2005 and again in 2007 the answer was no, for the reason that all the forests are rich forest. But then how come they are allocated to companies for coffee and rubber if they are rich forests?

The Chairman of Loc Bao commune was frank, “the villagers are very angry. The government has allocated forest to the companies… Why did the government say these forests are poor forest? The villagers tried (to get land) from the government without success. We requested allocation from the District authorities, but they passed it up the line to the Province. We don’t know what happened”.

Village 3 leader Mr K’Ba said “We don’t believe in the officers at District and Province level any more. The villagers cannot believe what they say.”

Hot Issues went to Binh Phuoc province to look at another possible trouble spot, where they visited forest being protected by veterans. A female veteran said “This is rich forest. The government has had many evaluations, saying that this is rich forest, primary forest, very important forest that could be used for education, for national heritage. It has been protected by ancestors for a long time and is ready to be handed over for the young generation to be protected. Now this kind of forest is being converted into poor forest so it can be re-classified for rubber.

A journalist from Binh Phuoc added “There is not much forest like this left. It remains only because the villagers have protected it. But now they plan to allocate it to companies for rubber plantations.”

As Professor Nguyen Ngoc Lung pointed out, “The process of conversion and classification is made by FIPI (the Forest Inventory and Planning Institute). This means that the Province has asked them to do this according to policy and regulations. The steps they follow seem correct, but they are only correct on paper. What they report as poor forest in reality is not, it is rich forest… We need everyone, as many people as possible, to speak out about this, not just the scientific class.”

Mr Do Manh Hung, Vice Head of the Social Issues Committee of the National Assembly added, “Almost all local governments so far are not implementing Resolution 28 which instructs them to take land back from enterprises to allocate to households who need it. Policies from government are clearly concerned with the plight of ethnic minorities from the North west, Central highlands and the South-west who lack land for cultivation, and who should be given priority for land.”

The programme finished with the clear written message that whilst Vietnam’s primary forests are being converted with official consent for rubber plantations and for logging, the Norway government and UN have contributed US$30 through REDD+ for their protection.

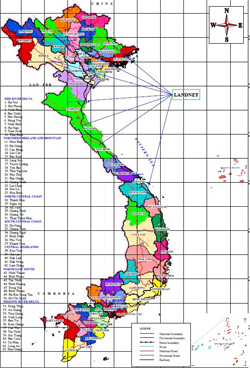

LANDNET

.jpg) This is “Village No. 3”, where Chau Ma people were resettled for the third time. Primary Forest & land next to their houses, up to mountain, is being used by private companies

This is “Village No. 3”, where Chau Ma people were resettled for the third time. Primary Forest & land next to their houses, up to mountain, is being used by private companies

(12).jpg) This is a house made by villagers themselves. Forest land next to their houses is being used and managed by Kinh people

This is a house made by villagers themselves. Forest land next to their houses is being used and managed by Kinh people

(6).jpg) The man in the photo is the Village Party Head. On the left is a house built by the State for his parents in gratitude for their contribution to national defense. However, they could not stay in the house due to the poor quality of construction. On the right is the house also built by the State for his family. This house was also poorly constructed, and after just a few years it has started to disintegrate. These houses are likely to collapse during heavy rains or typhoons . Most of the houses built by the state have no gardens

The man in the photo is the Village Party Head. On the left is a house built by the State for his parents in gratitude for their contribution to national defense. However, they could not stay in the house due to the poor quality of construction. On the right is the house also built by the State for his family. This house was also poorly constructed, and after just a few years it has started to disintegrate. These houses are likely to collapse during heavy rains or typhoons . Most of the houses built by the state have no gardens

(3).jpg) Abandoned State- provided housing

Abandoned State- provided housing

(1).jpg)

(1).jpg) Well for daily water supply

Well for daily water supply

.jpg) This is ancestral cemetery forest of Chau Ma people which they have preserved and protected for hundreds of years. Now it is being exploited by outsiders

This is ancestral cemetery forest of Chau Ma people which they have preserved and protected for hundreds of years. Now it is being exploited by outsiders

.jpg) Watershed forests converted above Dong Nai Power Plant No. 4 into plantations by rubber companies

Watershed forests converted above Dong Nai Power Plant No. 4 into plantations by rubber companies

.jpg) This is Dong Nai No 4 Hydropower in Lam Dong. Nearby watershed forests are being converted into production areas and allocated to different private companies for rubber and coffee plantations

This is Dong Nai No 4 Hydropower in Lam Dong. Nearby watershed forests are being converted into production areas and allocated to different private companies for rubber and coffee plantations

.jpg) Dong Nai No 4 Hydropower in Lam Dong

Dong Nai No 4 Hydropower in Lam Dong

.jpg) Primary forests being cleared and burned for rubber

Primary forests being cleared and burned for rubber

.jpg) Bao Lam rubber company sign

Bao Lam rubber company sign

.jpg) The primary and watershed forests (in the background) turned into production forests and rubber plantations

The primary and watershed forests (in the background) turned into production forests and rubber plantations

.jpg) Forests clear felled by companies, replaced with mixed cassava and rubber.

Forests clear felled by companies, replaced with mixed cassava and rubber.

[1] The companies’names: Tầm Vong; Tân Lập; Lê Dương, Đại Tiến; Hạ Tiến; Đài Loan; Hưng Yên, Cao Nguyên, Việt Tài; Bảo Lâm (SFE); Thủy điện Đồng Nai 4, Lâm trường Lộc Bắc and others.

.jpg)

(12).jpg)

(6).jpg)

(3).jpg)

(1).jpg)

(1).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)